- info@ghrd.org

- Mon-Fri: 10.00am - 06:00pm

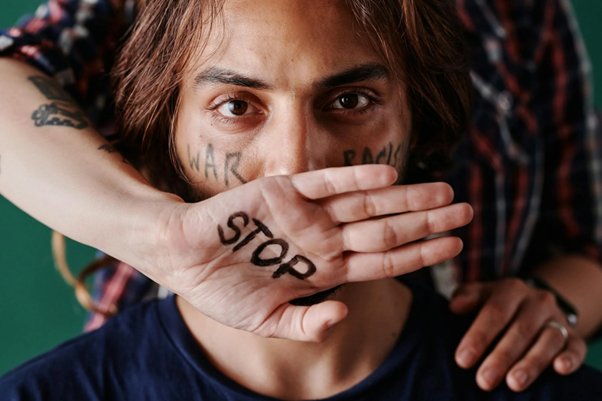

Shattering the Silence: Sexual Violence as a Means of War

Shattering the Silence: Sexual Violence as a Means of War

09-05-2024

Manouk Driessens

Women’s Rights Researcher,

Global Human Rights Defence.

Introduction

“Wherever armed conflicts have been fought on the land, women have been raped.” These are the words of ground-breaking feminist activist and author Susan Brownmiller. This assertion should by no means stir up some kind of cynical acquiescence in the entanglement of violent conflict and sexual violence against women. It is true, however, that the occurrence of sexual violence during wartime or in violent conflict has long been seen as an inevitable side effect of conflict. Simultaneously, the matter has long been taboo – and, in many ways, it still is.

Somewhat of a turning point only came about in the nineties when the world was left shocked by reports of systemic sexual violence in the Bosnian War, which affected more than 20,000 women and girls. As the phenomenon has been receiving more attention from scholars and activists, the paradigm is slowly shifting away from perceiving sexual violence against women in a conflict zone as a lamentable side effect of the violent context. Instead, it is increasingly recognised as a deliberate subjugation tactic, warranting urgent legal and humanitarian responses to ensure accountability and support for survivors.

Breaking The Cycle: Sexual Violence in Wartime

The use of large-scale sexual violence to obtain a specific goal can even be found in ancient mythology. In the early history of newly founded Rome, Romulus and his men were worried about the survival of the city’s population given the scarcity of women inhabitants. Desperate to fix this, the Romans lured the Sabines to a festival, where they fought off the men and forcibly took the Sabine women to become their wives instead. This story is known as the raptio or rape of the Sabine women. The Latin word raptio translates to abduction, but in a context pertaining to women as the object of raptio, this implies sexual violence.

While the abduction of the Sabine women might be a myth, the central theme is hardly fiction. Still today, similar and much more violent scenes mark the lives of many girls and women living in conflict areas. In the case of some, this is a daily reality for protracted periods of time – think of Sudan, Mali, Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria, Myanmar, and many more.

Delving back into history, the Spanish Civil War can be cited as the first instance of wartime rape being deliberately used as a weapon towards women. The shock troops of General Franco’s Nationalists systematically raped and tortured women to punish their opponents. Shortly after, hundreds of thousands of women fell victim to sexual violence during World War II, from mass rape by the Red Army in Occupied Germany, to the system of sexual slavery that the Japanese Army established.

Today, nearly a century later, the latest report of the UN Office for the Special Representative for Sexual Violence in Conflicts (SRSG-SVC) makes mention of at least 49 parties for which the United Nations has credible evidence proving they resort to tactics of sexual violence against the civilian population of their country. Given the high standards of collecting evidence for the United Nations, this figure remains a conservative assessment, with the ‘dark number’ undoubtedly much higher.

Beyond Sexuality: Deconstructing Wartime Sexual Violence

Although we are dealing with sexual violence, experts largely agree that there is nothing sexual about rape. Susan Brownmiller argued as early as 1975 that rape has hardly anything to do with satisfying a sexual desire. Many academics have corroborated this, asserting that sexual desire cannot explain the brutality of wartime rape nor its high occurrence rate.

In her notable work Against our will: Men, women and rape (1975), Brownmiller explains how sexual violence should instead be viewed as a process of intimidation that keeps women in a state of fear. This ultimate submission of the victims gives the perpetrator an overwhelming sense of dominance and power. In the same vein, Dr Denis Mukwege, a renowned expert in the field of sexual violence in armed conflict, has explained how rape carried out by militias in armed conflict is part of a deliberate strategy based on dehumanisation and destruction of the victim.

The Forgotten Victims: Weaponising the Impact of Sexual Violence

Having established that sexual violence should not be viewed as an inevitable by-product of violent conflict, and that the sexual dimension is not a prominent component of the story, a more relevant approach is to view wartime sexual violence for the deliberate tactic that it is. In short, sexual violence is a weapon of war. Sexual violence by armed actors can be the result of the perpetrator’s individual decision, in which case the armed actor does not necessarily view this act as part of a larger strategy. On a more organised scale, however, the patterns become more visible.

The impact of widespread sexual violence in a context that is already precarious can hardly be overestimated. Time and time again, it has proven to be a tool of terror, demoralisation and subjugation. What makes rape a particularly insidious weapon is the perceived cost-effectiveness, from the perspective of the perpetrators, in combination with its destructive effects. This trail of devastation has to be considered on a multitude of levels – physical, psychological, and social – both for the individual victim and the entire community.

First and foremost, if they survive the attack, victims are left with horrific physical injuries as a result of the undergone violence. Survivors’ bladders or rectums are often damaged to the extent that it causes severe health issues and even further social isolation. Unwanted pregnancies as a result of wartime rape often lead to illegal, highly dangerous abortions. This closely ties in with the enormous psychological burden that the trauma and stigma bring upon the survivors, which explains the consequently high levels of suicide.

Beyond individual victims, entire communities suffer in the aftermath of systematic sexual violence. With victims and their families subjected to overwhelming shame, systematic sexual violence can leave a community destroyed and deserted. In the most extreme case, sexual violence is used for purposes of genocide and ethnic cleansing, as was the case in Rwanda and Bosnia. Forced impregnation of women who belong to a specific group is not only a form of torture that brings a powerful stigma upon the victims, but also physically hinders the procreation of the targeted group.

Justice Denied: The International Legal Framework

Sexual violence has long been altogether neglected in the realm of international law. Important legal sources in human rights law make no explicit mention of sexual violence, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention against Torture, and the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This way, effective protection is undermined because the interpretation is left open – even if common sense dictates that sexual violence falls under ‘cruel’ or ‘inhumane treatment’.

In the context of armed conflict, international humanitarian law (IHL) adds another body of law to the legal questions surrounding sexual violence. Investigating IHL quickly reveals that treaty law also leaves a lot to be desired in the realm of protection against sexual violence. In the Geneva Conventions and its Additional Protocols, the references made to sexual violence only mention a prohibition of rape, without providing further clarification. This makes for a basis of treaty law that is too narrow and falls short of covering the complexities of sexual crimes against women.

As a result of the general principle of law nullum crimen sine lege, nulla poena sine lege, it is essential that a crime is well-defined as such in order for punishment to be possible. In this light, important steps were taken by the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and Rwanda (ICTR) towards the conceptualisation of wartime sexual violence as a means of war, and hence as a threat to international peace and security itself.

In 2007, the ICTY set an important precedent by convicting Mr Dragan Zelenović for sexual violence as a crime against humanity as well as a violation of the customs of war. The Tribunal highlighted the importance of recognising sexual violence as a grave human rights violation. The 1998 case against Mr Jean-Paul Akayesu by the ICTR represented the first instance where an individual was convicted for genocide. In its judgment, the ICTR considered sexual violence as a form of genocide in case of the intent to destroy a targeted group. It thereby set an important precedent in recognising, as well as prosecuting, sexual violence as a serious international crime.

Grave sexual violence, including but not limited to rape, is recognised by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The Rome Statute explicitly lists “rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilisation, or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity” as war crimes, as well as crimes against humanity. While this progressive inclusion of sexual violence in the Rome Statute prompted high hopes for many, it has not been able to live up to expectations.

Covered in Silence: A Problem of Impunity

Although the prohibition of rape and sexual violence as a means of war is incorporated in the international legal framework, the high rate of persisting sexual violence clearly indicates that the system is still falling short. This can undoubtedly be attributed to a combination of multiple factors, from flaws inherent to structures where state sovereignty is so centrally present to a systematic lack of attention to women’s issues. The few existing convictions to date do not outweigh the general culture of impunity when it comes to perpetrators (and instigators) of sexual violence in wartime.

Even the problem of impunity is complicated because, for there to be an end to impunity, there first has to be an end to silence – a deafening silence which in itself already comprises multiple layers. Sexual violence is the most personal of violations and it remains the most underreported crime. In conflict zones, this trend is further exacerbated. The trauma and shame that victims experience, the dread of not being believed, and in some cases even a fear of punishment in case they speak up, foster silence. And this silence fosters impunity. And the culture of impunity fosters even more silence.

There are survivors who do find the courage to speak up. This act of courage is seldomly rewarded, as it often leads to additional hardships that worsen the situation. When Dr Mukwege received the Nobel Prize together with Nadia Murad, Special Representative for Sexual Violence in Conflict, Pramila Patten put it this way: “Many victims who survive sexual violence do not survive its social repercussions. Rape is still the only crime for which a society is more likely to stigmatise the victim, than to punish the perpetrator.”

Conclusion: Moving Forward Towards Healing and Prevention

They say all is fair in love and war, but this leaves a bitter taste. How to proceed, then? Even if improving the situation will take a lot of time and effort, every article written, every witness and survivor stepping forward, along with every conviction, contribute to weakening the system of silence and impunity that perpetuates sexual violence as a means of war. On the bright side, the taboo surrounding rape has been diminishing, and emerging practice shows progress. That being said, the extent to which sexual violence is still perpetrated indicates that we still have a long road ahead of us.

The need for global action is urgent. Mentalities need to change, and the law needs to follow suit – starting yesterday rather than tomorrow. The wheels of justice turn slowly. Societies need to be reorganised, away from patriarchal structures and incorporating the newly acquired attention that women’s issues have long lacked. More relevant instruments, such as a UN Treaty on women and sexual violence, are long overdue. However, for this to one day become reality, political will is of paramount importance.

The international legal system must become more effective, but this will not be sufficient. A broad outlook on justice is indispensable for survivors and the recognition they need, even if their pain cannot be undone. The starting point of a collective response should be rooted in empathy and solidarity with the victims of wartime sexual violence. And then, hopefully soon enough, the circle of silence will be broken.

References

Susan Brownmiller, Against our will: Men, women and rape (Simon & Schuster 1975).

This article focuses on sexual violence against women without intending to detract from the struggle that men and boys face when they fall victim to sexual violence. Sexual violence against men is a topic in its own right, with its own underlying dynamics that should be expanded upon in a separate article.

Janine Clark, Rape, sexual violence and transitional justice challenges: Lessons from Bosnia Herzegovina (Routledge 2017).

Rebecca Zorach, ‘Dangerous to beauties: The Sabine women, symbolic conquest and classicism’ Adaptation: University of Chicago (2008) <https://smartmuseum.uchicago.edu/adaptation/2008/03/20/dangerous-to-beauties-the-sabine-women-symbolic-conquest-and-classicism/>.

Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict (SRSG-SVC) ‘Report of the United Nations Secretary-General on Conflict-Related Sexual Violence’ (6 July 2023) S/2023/413, 8-21.

Christina Lamb, Our bodies, their battlefield: What war does to women (William Collins 2020) 203.

William Benedict Russell III and Stewart Waters, ‘Analyzing human rights violations during the World War II era’ (2012) 76 Social Education 6.

Office of the SRSG-SVC (n 4) 4; 28-32.

Susan Brownmiller, Against our will: Men, women and rape (Simon & Schuster 1975).

Dara Kay Cohen, Amelia Hoover Green and Elisabeth Jean Wood, ‘Wartime sexual violence: Misconceptions, implications, and ways forward’ (2013, February) Special Report 323 USIP.

Claudia Card, ‘Rape as a weapon of war’ (1996) 21 Medical Aspects of Human Sexuality 3, 5; Maria Eriksson Baaz and Maria Stern, ‘Curious erasures: The sexual in wartime sexual violence’ (2018) 20 IFJP 3, 295.

Dr Denis Mukwege in conversation with Christina Lamb, as included in Lamb (n 5) 283; 304-305.

Card (n 10) 5-6.

Mukwege in Lamb (n 5) 304-305.

Mukwege in Lamb (n 5) 304-305.

Lamb (n 5) 392.

Mukwege in Lamb (n 5) 304-305; See also Card (n 10); Maria B Olujic ‘Embodiment of terror: Gendered violence in peacetime and wartime in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina’ 12 Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1; Jocelyn Kelly ‘Rape in war: Motives of militia in DRC’ (2010, June) Special Report 243 United States Institute of Peace.

Beyond the genocides in Rwanda and Bosnia and Herzegovina, other lamentable examples of wartime rape being instrumentalised towards ethnic cleansing can be found in e.g. Bangladesh and Croatia. See e.g.: Card (n 10); Bülent Diken and Carsten Bagge Lausten, ‘Becoming abject: Rape as a weapon of war’ (2005) 11 Body & Society 1; Christina Ewig, Myra Marx Ferree and Ali Mari Tripp, A M (eds), Gender, violence, and human security: Critical feminist perspectives (New York University Press 2013); Dara Kay Cohen, Rape during civil war (Cornell University Press 2016).

Riki Van Boeschoten ‘The trauma of war rape: A comparative view on the Bosnian conflict and the Greek civil war’ (2003) 14 History and Anthropology 1; Diken and Lausten (n 17).

There is a lot to be said about the legal frameworks surrounding rape or violence against women more generally. In most countries, these are severely lacking. For the topic of sexual violence in wartime specifically, the focus of this article is on the international legal framework.

Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (GCIV) (adopted 12 August 1949, entered into force 21 October 1950) common art 3(1)(c); art 27; Theodor Meron, ‘Rape as a crime under International Humanitarian Law’ (1993) 87 AJIL 3, 425.

Jennifer Park, ‘Sexual violence as a weapon of war in International Humanitarian Law’ (2007) 3 IPPR 1, 14.

Park (n 21) 13.

Prosecutor v Dragan Zelenović, [2007] ICTY IT-96-23/2 (ICTY Appeals Chamber, 23 February 2007).

Prosecutor v Jean-Paul Akayesu, [1998] ICTR-96-4-T (ICTR Trial Chamber, 2 September 1998).

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) (adopted 17 July 1998, entered into force 1 July 2002) art 8(2)(b)(xxii).

Rome Statute of the ICC (n 25) art 7(1)(g).

Tanja Altunjan, ‘The International Criminal Court and sexual violence: Between aspirations and reality’ (2021) 22 GLJ 1, 878.

Lamb (n 5) 391-392.

‘Remarks of SRSG-SVC Pramila Patten at the event: “Sexual Violence as a Weapon of War: Reflections on the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize”, Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), 11 December 2018’ (OSRSG-SVC, 11 December 2018) <https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/statement/remarks-of-srsg-svc-pramila-patten-at-the-event-sexual-violence-as-a-weapon-of-war-reflections-on-the-2018-nobel-peace-prize-peace-research-institute-oslo-prio-11-december-2018/>.

Van Boeschoten (n 18); Altunjan (n 27) 878.

Search

ABOUT US

Global Human Rights Defence (GHRD) is a dedicated advocate for human rights worldwide. Based in The Hague, the city of peace and justice. We work tirelessly to promote and protect the fundamental rights of individuals and communities. Our mission is to create a more just and equitable world, where every person's dignity and freedoms are upheld. Join us in our journey towards a brighter future for all.

ALL CONTACTS

-

Riviervismarkt 5-unit 2.07

2513 AM The Hague - Phone +31 62 72 41006

- info@ghrd.org

-

10:00am - 06:00pm

Saturday & Sunday Closed - Bank Details: NL69ABNA0417943024

SUBSCRIBE

Stay informed and be part of change - Subscribe to our newsletter today!

- Copyright of ghrd 2023. Powered by Desmantle Studio.

Leave a Reply